|

CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION

|

|

|

Even more dangerous are the “modernization” projects when a local authority or the priest decides to throw out everything that is old, damaged, looks bad, or “doesn’t work anymore.” For this reason a countless number of religious objects, not only organs, have been lost.

In addition, migration to the US or nearby large cities has drastically reduced the population in many communities. Along with the shortage of priests this means that many churches are rarely open. As a consequence, the local people have lost contact with the furnishings of their churches. When they accompany us to the choir loft, some will admit that this is the first time they have ever been up there or seen the organ.

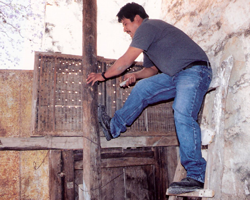

More recently, the earthquakes of 2017 did not seriously damage any Oaxaca organs, other than jiggling pipes out of place or causing heavy pipes to fall on smaller ones. However, many domes over the choir lofts were cracked, necessitating covering the organ (Jalatlaco) or lowering it in pieces from the choir loft to be stored elsewhere in the church (Lachiguiri) before beginning the repair work. Such projects are now supervised by the INAH, unlike in 1999 before conservation standards were defined and enforced. Then we heard of globs of mortar falling into the open pipes as the masons worked above the organ and of an organ which fell apart after being lowered with ropes then raised up again to the choir loft.

San Matías Jalatlaco. The organ was covered in 2019 for repair projects related to the 2017 earthquakes. |

Santa María Suchixtlán, part of the organ’s projects façade. The organ fell apart in 1999 when it was raised up to the choir loft on ropes. The pipes and many components were scattered around in the village but were at least preserved and are now stored in the church. |

The IOHIO has made hundreds of visits to check up on the 61 unrestored organs, and we always hope that there won’t be unpleasant surprises awaiting us if some years have passed (such as “where is the organ?”). Our activities are supported by a letter of authorization from the director of the INAH Oaxaca and the permission of the priest and/or the municipal authorities.

The sequence of our work is as follows:

1. We set up an appointment in advance with the relevant authorities. During our first years of work, there were few functioning telephones and paved roads, so we often just went and hoped for the best. With luck we could see the organ, but sometimes the person with the key to the choir loft was in his field and not due back until sundown. Succeeding visits have been easier because of improved roads and communication and previous contacts in the community.

2. Upon arriving, we speak with the municipal authority or the priest about the IOHIO and the work we intend to do, the Oaxaca organs in general and their organ in particular, and the importance of conserving historic church art as part of their local heritage. We distribute brochures and CDs, something tangible rather than just talk. We also clarify that the work is supported by our organization and will cost them nothing, always a topic of concern.

3. If a previously registered organ is no longer in the church, usually removed during repair work and then not moved back, we look for it elsewhere – in the sacristy, store rooms, or nearby buildings. We then return it to its original position or to another safe place in the church.

|

|

|||

| San Juan Teitipac | San Pedro Quiatoni |

Santa María Peñoles

4. Conservation work begins with a basic cleaning of the choir loft or other area where the organ is located. Most of the organs are located in rural communities, have not been played for at least 50 years, and were usually filthy during our first visit. Since filth attracts vermin, the deterioration would feed on itself. Besides this, if the organ has been abandoned or just used to store junk, the community would not regard it as an object of value which merits protection. Therefore, one of our main goals has always been to make the organ look more presentable at the end of the day.

At least one representative of the municipal government or the church is on hand to observe our work. They often pitch in to help by sweeping, carrying buckets of water up and down the stairs, and removing useless objects and garbage from the organ area. Our activity may attract 20 or more curious men, women, and children from the community, most of whom have never been up to the choir loft.

5. We clean out the case, which may have objects related to the organ (pieces of moldings, carved decorations, small bent pipes) or not (candles, papers, flower pots).

This can be an unpleasant job if it has been inhabited by birds or rodents.

Rats’ nests inside the organ case

|

|

|||

If a bird falls into one of the large open pipes, it will never be able to escape. We have found more than a dozen bird carcasses in large façade pipes.

|

Scorpion skins |

We wipe off the interior wooden components, the keys and the keyboard mechanism, the wind chest, and the pipes. The organ case and bellows are dusted or vacuumed.

|

|

6. Throughout the process we analyze and document each component of the organ with photographs, measurements, and observations, which are registered in the IOHIO’s data base.

|

7. We reassemble the instrument and attach loose pieces of the case whenever possible, since otherwise they may disappear. Very small or damaged pipes or other stray components are stored in labeled boxes inside the organ case for safekeeping.

8. Sometimes we find music manuscripts or old band instruments and call in specialists to analyze and catalog them.

9. We talk to the local people who have drifted up into the choir loft about the organ and how it works, and we ask them questions about their community. They in turn want to know if the organ can be fixed, how much will it cost, and how it could be financed. The most satisfying moment of the day is when we “present” the organ in an improved, more dignified state. Sometimes the change may be dramatic, and the people are amazed by its beauty and the unexpected link to the world of their ancestors who commissioned the organ’s constructions many years ago. This we hope is the best guarantee that the organ will be safe and properly respected.

|

|

Nuestra Señora del Patrocinio (Oaxaca City)

|

|

San Miguel Ahuehuetitlan

|

|

San Mateo Capulalpan

|

|

Santa María Ejutla

The last step is to leave plastic-encased labels on or near each organ. The first shows the logos of SECULTA/INAH (the Secretaría de Cultura y las Artes and the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, both federal institutions) and the corresponding Diocese, representing their authority as protectors of the national heritage. It states: “The historic organ of (the name of the community) is part of the national patrimony and is protected by the Federal Law for Archeological, Artistic and Historical Zones and Monuments. Take care of it because it is a part of the history of your community.”

San Miguel Chicahua

A second label bears the logo of the IOHIO and includes the specific or approximate date of the organ’s construction, the name of the builder if known, special characteristics of the organ, a list of similar organs, and what the community should and should not do to protect and conserve it:

YES - restrict access to the choir loft and keep the area clean

YES - install screens on the windows and doors of the church to keep out birds and other animals

YES - cover the organ during construction or remodeling projects in the church

NO - clean the organ, except to dust it off

NO - remove any pieces of the organ

NO - store objects unrelated to the organ in the interior of the case or on top of the bellows

Our principal objective is to inform the people in the community that the organ has its own rights and that they cannot do with it as they please (“fix” it, clean or paint it, sell it, dismember it for its parts, or destroy it). Copies of these labels are left in the municipal or church office as a reference.

In particular cases, we construct replacement keyboard covers for organs which have lost them and as a result, have lost some or all of their keys. These wooden covers are painted to approximate the original color of the case.

Sta. María Tlacolula before the restoration in 2014

San Juan Bautista Teposcolula

We install posts with rope to establish an off-limits zone for some of the decorated organs. The intention is to protect them from curious children in catechism classes or musicians in the choir loft that might be tempted to pick and scratch at the paint, push and pull the stops, or fidget with the case.

The table organ in San Pedro Cholula was found on the church floor full of old papers. Its table was upstairs in the choir loft. One of the bellows had been used for a roof repair.

The organ in San Juan Teitipac was converted into a confessional in the 1950s |

The upper case of the organ in Santiago Ihuitlan Plumas has been used as an altar piece (retablo) |

The table organ in San Juan Bautista Coixtlahuaca was used as a piece of furniture in the priest’s bedroom in the 1950s. A shelf was installed and a drawer replaced the keyboard.

Ongoing maintenance includes keeping the choir loft, case and keyboard clean, which unfortunately includes removing animal droppings. We tune the trumpets and adjust any sticky keys before a concert. When necessary we hire a professional restorer to clean the case, fumigate for woodworm, or make technical adjustments. We are alerted by the authorities if there is pending work in the church which might affect the organ. Most important for keeping these mechanical action instruments in good working order is to play them regularly.

|

|

|||

| Tlacochahuaya: Tuning and voicing the pipes | Updating the labels |

|

|

|||

| Zautla: cleaning the organ |

Adjusting the bellows |

The table organ in Santiago Tlazoyaltepec, built in 1724 by Marcial Ruiz Maldonado, was severely damaged in January 2013. A reflector lamp had been left face down on top of a pile of old documents stored inside the case and was switched on inadvertently. The lamp overheated, burned through the papers, and consumed the wind chest of the organ. The smoke pouring out of the church alerted the townspeople who happened to be in a meeting next door. They located the source of the fire through the dense smoke, ran upstairs to the choir loft, and extinguished the fire with their bottles of soda. If not for this Sunday meeting with the authorities gathered right next to the church, it is likely that the organ and perhaps the entire church with its wooden roof might have been destroyed. Fortunately the chest had been carefully documented and photographed and if necessary, could be rebuilt.

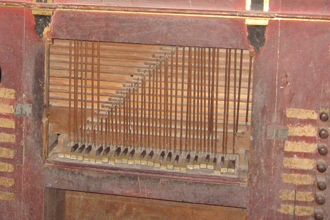

In December 2018 the 18th century wind chest of the organ in the Basílica de la Soledad was returned to Oaxaca, a process initiated by the IOHIO and carried out by the offices of the INAH in Oaxaca and Puebla. It had been stored in the organbuilder’s home in Puebla since the restoration was finished in 2000, because at the time it turned out to be more convenient to build a new chest rather than restore the old one. This large piece (2.30 m. side to side) is the brain of the organ and critically important. It probably would have been forgotten in Puebla if the IOHIO had not alerted the INAH which ordered its return to the Basilica.

|

|

|||

| Wind chest now stored in the Basílica de la Soledad | The fourth bellows of the organ stored under the wind chest |

The three functioning bellows of the Soledad organ

Privacy Policy Copyright � 2024 Instituto de Órganos Históricos de Oaxaca, A.C. � Web Design by Ambidextro |